Ki Tisa

The 120-Day Version Of The Human Story

A single drop of seawater, analyzed in the laboratory, will reveal the characteristics of billions of her sisters; indeed, it will tell you much about every drop in every ocean on earth.

The same is true of history. On the one hand, each period is unique, each year, day and moment distinct in content and character. And yet, as we often recognize, the story of an individual life may tell the story of a century, and the events of a single generation may embody those of an entire era. On the surface, time may more resemble the disparate terrain of land than it does the uniform face of the sea; but once you strip away the externalities of background and circumstance, a drop in the ocean of time will reflect vast tracts of its waters and, ultimately, its entire expanse.

We, who travel the terrestrial surface of time, know it as a succession of events and experiences. We traverse its rises and slumps, its deserts and wetlands, its smooth plains and rocky passes. To us, the universal nature of the moment lies buried deep beneath its more immediate significance; to us, the moment yields not the totality of life and history, only those specific elements and facets thereof which it embodies.

But there are also vistas of a more inclusive nature, landscapes of such diversity and impact that they are virtual mini-worlds of their own. There are stretches in the journey of an individual or a people in which the all-reflectiveness of the moment rises to the surface, in which a series of events offer a condensed version of the entire universe of time.

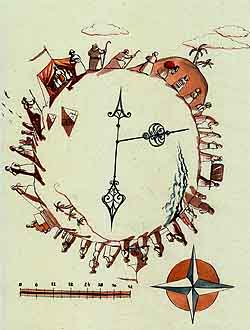

One such potent stretch of time was a 120-day period in the years 2448–9 from Creation (1313 BCE). The events of this period, experienced by the Jewish people soon after their birth as a nation, choreograph the very essence of the human story—the basis, the process and the end goal of life on earth. The hundred and twenty days from 6 Sivan 2448 to 10 Tishrei 2449 contained it all: the underpinnings of creation, the saga of human struggle, and the ultimate triumph which arises from the imperfections and failings of man.

The Events

On 6 Sivan 2448, the entire people of Israel gathered at Mount Sinai to receive the Torah from the Almighty. There they experienced the revelation of G‑d, and heard the Ten Commandments, which encapsulate the entire Torah. The following morning Moses ascended the mountain, where he communed with G‑d for forty days and forty nights and received the Torah proper, the more detailed rendition of G‑d’s communication to humanity.

At the end of Moses’ (first) forty days on Mount Sinai, G‑d gave him two tablets of stone, the handiwork of G‑d, upon which the Ten Commandments were engraved by the finger of G‑d. But in the camp below, the Jewish people were already abandoning their newly made covenant with G‑d. Reverting to the paganism of Egypt, they made a calf of gold and, amidst feasting and hedonistic disport, proclaimed it the god of Israel.

"G‑d said to Moses: Descend, for your people, which you have brought up from the land of Egypt, have been corrupted; they have quickly turned from the path that I have commanded them . . .

Moses turned and went down from the mountain, with the two tablets of testimony in his hand . . . When Moses approached the camp and saw the calf and the dancing . . . he threw the tablets from his hands and shattered them at the foot of the mountain."

It was the 17th of Tammuz.

Moses destroyed the idol and rehabilitated the errant nation. He then returned to Sinai for a second forty days, to plead before G‑d for the forgiveness of Israel. G‑d acquiesced, and agreed to provide a second set of tablets to replace those which had been broken in the wake of Israel’s sin. These tablets, however, were not to be the handiwork of G‑d, but of human construction:

"G‑d said to Moses: Carve yourself two tablets of stone, like the first; and I shall inscribe upon them the words that were on the first tablets which you have broken . . . Come up in the morning to Mt. Sinai, and present yourself there to Me on the top of the mountain."

Moses ascended Sinai, for his third and final forty days atop the mountain, on 1 Elul. G‑d had already forgiven Israel’s sin, and now a new and invigorated relationship between Him and His people was to be rebuilt on the ruins of the old. On 10 Tishrei we received our second set of the Ten Commandments, inscribed by G‑d upon the tablets carved by Moses hand.

Thus, we have three forty-day periods, and three corresponding states of Torah: the first tablets, the broken tablets and the second tablets. These embody the foundation of our existence, the challenge of life and the ultimate achievement of man.

The Plot

Our sages point out that the opening verse of the Torah’s account of creation, Bereishit bara Elokim . . . (“In the beginning G‑d created the heavens and earth”), begins with the letter beit, the second letter of the Hebrew alphabet. This is to teach us that there is an alef that comes before the beit of the created existence: that creation is not an end in itself, but comes to serve a principle which precedes it in sequence and substance.

The pre-Genesis alef is the alef of Anochi Hashem Elokecha . . . (“I am the L‑rd your G‑d . . .”)—the first letter of the Ten Commandments. Torah is G‑d’s preconception of what life on earth should be like; the basis and raison d’etre of creation is that we develop ourselves and our environment to this ideal.

But G‑d wanted more. More than the realization of His original blueprint for existence, more than the falling into place of a preprogrammed perfection. More than a “first tablets” world that is wholly the handiwork of G‑d.

A created entity, by definition, has nothing that is truly its own: all the tools, potentials and possibilities it possesses have been given to it by its creator. But G‑d desired that the human experience should yield a profit beyond what is projected—or even warranted—by His initial investment in us. So He created us with the vulnerabilities of the human condition.

He created us with the freedom to choose, and thus with the potential for failure. When we act rightly and constructively, we are behaving according to plan, and realizing the potential invested within us by our Creator. But when we choose to act wrongly and destructively, we enter into a state of being that is not part of the plan of Torah—indeed, it is the antithesis of what Torah prescribes. Yet this state of being is the springboard for teshuvah (return)—the power to rise from the ruins of our fall to a new dimension of perfection, a perfection unenvisionable by our untarnished past.

This is how chassidic teaching explains G‑d’s creation of the possibility of evil. This is “His fearsome plot upon the children of man.” The soul of man is a spark of G‑dliness, inherently and utterly good; in and of itself, it is in no way susceptible to corruption. Its human frailties are nothing less than a contrived plot, imposed upon it in total contrast to its essential nature.

If the first tablets are the divine vision of creation, the broken tablets are our all-too-familiar world—a world that tolerates imperfection, failure, even outright evil. It is a world whose first tablets have been shattered—a world gone awry of its foundation and its true self, a world wrenched out of sync with its inherent goodness.

The broken tablets are a plot contrived by the Author of existence to allow the possibility for second tablets. Every failing, every decline can be exploited and redirected as a positive force. Every breakdown of the soul’s “first tablets” perfection is an opportunity for man to carve for yourself a second set, in which the divine script is chiseled upon the tablets of human initiative and creation. A second set which includes an entire vista of potentials that were beyond the scope of the first, wholly divine set.

"G‑d said to Moses: Do not be distressed over the first tablets, which contained only the Ten Commandments. In the second tablets I am giving you also halachah, midrash and aggadah.

Had Israel not sinned with the Golden Calf, our sages conclude, they would have received only the five books of Moses and the book of Joshua. For as the verse says, “Much wisdom comes through much grief.”

Remembered and Enacted

These hundred and twenty days have left a lasting imprint on our experience of time. For the Jewish calendar does far more than measure and mark time; in the words of the book of Esther, “These days are remembered and enacted.” The festivals and commemorative dates that mark our annual journey through time are opportunities to reenact the events and achievements which they remember.

Every Shavuot, we once again experience the revelation at Sinai and our acquisition of the blueprint and foundation of our lives. Every year on the 17th of Tammuz, we once again deal with the setbacks and breakdowns epitomized by the events of the day. The month of Elul and the first ten days of Tishrei, corresponding to Moses’ third 40-day stay on Mount Sinai, are, as they were then, days of goodwill between G‑d and man—days in which the Almighty is that much more accessible to all who seek Him.

And Yom Kippur, the holiest and most potent day of the year, marks the climax of the 120-day saga. Ever since the day that G‑d gave the second tablets to the people of Israel, this day is a fountainhead of teshuvah: the source of our capacity to reclaim the deficiencies of the past as fuel and momentum for the attainment of new, unprecedented heights; the source of our capacity to exact a profit from G‑d’s volatile and risky investment in human life.

Based on the teachings of the Lubavitcher Rebbe.

A single drop of seawater, analyzed in the laboratory, will reveal the characteristics of billions of her sisters; indeed, it will tell you much about every drop in every ocean on earth.

The same is true of history. On the one hand, each period is unique, each year, day and moment distinct in content and character. And yet, as we often recognize, the story of an individual life may tell the story of a century, and the events of a single generation may embody those of an entire era. On the surface, time may more resemble the disparate terrain of land than it does the uniform face of the sea; but once you strip away the externalities of background and circumstance, a drop in the ocean of time will reflect vast tracts of its waters and, ultimately, its entire expanse.

We, who travel the terrestrial surface of time, know it as a succession of events and experiences. We traverse its rises and slumps, its deserts and wetlands, its smooth plains and rocky passes. To us, the universal nature of the moment lies buried deep beneath its more immediate significance; to us, the moment yields not the totality of life and history, only those specific elements and facets thereof which it embodies.

But there are also vistas of a more inclusive nature, landscapes of such diversity and impact that they are virtual mini-worlds of their own. There are stretches in the journey of an individual or a people in which the all-reflectiveness of the moment rises to the surface, in which a series of events offer a condensed version of the entire universe of time.

One such potent stretch of time was a 120-day period in the years 2448–9 from Creation (1313 BCE). The events of this period, experienced by the Jewish people soon after their birth as a nation, choreograph the very essence of the human story—the basis, the process and the end goal of life on earth. The hundred and twenty days from 6 Sivan 2448 to 10 Tishrei 2449 contained it all: the underpinnings of creation, the saga of human struggle, and the ultimate triumph which arises from the imperfections and failings of man.

The Events

On 6 Sivan 2448, the entire people of Israel gathered at Mount Sinai to receive the Torah from the Almighty. There they experienced the revelation of G‑d, and heard the Ten Commandments, which encapsulate the entire Torah. The following morning Moses ascended the mountain, where he communed with G‑d for forty days and forty nights and received the Torah proper, the more detailed rendition of G‑d’s communication to humanity.

At the end of Moses’ (first) forty days on Mount Sinai, G‑d gave him two tablets of stone, the handiwork of G‑d, upon which the Ten Commandments were engraved by the finger of G‑d. But in the camp below, the Jewish people were already abandoning their newly made covenant with G‑d. Reverting to the paganism of Egypt, they made a calf of gold and, amidst feasting and hedonistic disport, proclaimed it the god of Israel.

"G‑d said to Moses: Descend, for your people, which you have brought up from the land of Egypt, have been corrupted; they have quickly turned from the path that I have commanded them . . .

Moses turned and went down from the mountain, with the two tablets of testimony in his hand . . . When Moses approached the camp and saw the calf and the dancing . . . he threw the tablets from his hands and shattered them at the foot of the mountain."

It was the 17th of Tammuz.

Moses destroyed the idol and rehabilitated the errant nation. He then returned to Sinai for a second forty days, to plead before G‑d for the forgiveness of Israel. G‑d acquiesced, and agreed to provide a second set of tablets to replace those which had been broken in the wake of Israel’s sin. These tablets, however, were not to be the handiwork of G‑d, but of human construction:

"G‑d said to Moses: Carve yourself two tablets of stone, like the first; and I shall inscribe upon them the words that were on the first tablets which you have broken . . . Come up in the morning to Mt. Sinai, and present yourself there to Me on the top of the mountain."

Moses ascended Sinai, for his third and final forty days atop the mountain, on 1 Elul. G‑d had already forgiven Israel’s sin, and now a new and invigorated relationship between Him and His people was to be rebuilt on the ruins of the old. On 10 Tishrei we received our second set of the Ten Commandments, inscribed by G‑d upon the tablets carved by Moses hand.

Thus, we have three forty-day periods, and three corresponding states of Torah: the first tablets, the broken tablets and the second tablets. These embody the foundation of our existence, the challenge of life and the ultimate achievement of man.

The Plot

Our sages point out that the opening verse of the Torah’s account of creation, Bereishit bara Elokim . . . (“In the beginning G‑d created the heavens and earth”), begins with the letter beit, the second letter of the Hebrew alphabet. This is to teach us that there is an alef that comes before the beit of the created existence: that creation is not an end in itself, but comes to serve a principle which precedes it in sequence and substance.

The pre-Genesis alef is the alef of Anochi Hashem Elokecha . . . (“I am the L‑rd your G‑d . . .”)—the first letter of the Ten Commandments. Torah is G‑d’s preconception of what life on earth should be like; the basis and raison d’etre of creation is that we develop ourselves and our environment to this ideal.

But G‑d wanted more. More than the realization of His original blueprint for existence, more than the falling into place of a preprogrammed perfection. More than a “first tablets” world that is wholly the handiwork of G‑d.

A created entity, by definition, has nothing that is truly its own: all the tools, potentials and possibilities it possesses have been given to it by its creator. But G‑d desired that the human experience should yield a profit beyond what is projected—or even warranted—by His initial investment in us. So He created us with the vulnerabilities of the human condition.

He created us with the freedom to choose, and thus with the potential for failure. When we act rightly and constructively, we are behaving according to plan, and realizing the potential invested within us by our Creator. But when we choose to act wrongly and destructively, we enter into a state of being that is not part of the plan of Torah—indeed, it is the antithesis of what Torah prescribes. Yet this state of being is the springboard for teshuvah (return)—the power to rise from the ruins of our fall to a new dimension of perfection, a perfection unenvisionable by our untarnished past.

This is how chassidic teaching explains G‑d’s creation of the possibility of evil. This is “His fearsome plot upon the children of man.” The soul of man is a spark of G‑dliness, inherently and utterly good; in and of itself, it is in no way susceptible to corruption. Its human frailties are nothing less than a contrived plot, imposed upon it in total contrast to its essential nature.

If the first tablets are the divine vision of creation, the broken tablets are our all-too-familiar world—a world that tolerates imperfection, failure, even outright evil. It is a world whose first tablets have been shattered—a world gone awry of its foundation and its true self, a world wrenched out of sync with its inherent goodness.

The broken tablets are a plot contrived by the Author of existence to allow the possibility for second tablets. Every failing, every decline can be exploited and redirected as a positive force. Every breakdown of the soul’s “first tablets” perfection is an opportunity for man to carve for yourself a second set, in which the divine script is chiseled upon the tablets of human initiative and creation. A second set which includes an entire vista of potentials that were beyond the scope of the first, wholly divine set.

"G‑d said to Moses: Do not be distressed over the first tablets, which contained only the Ten Commandments. In the second tablets I am giving you also halachah, midrash and aggadah.

Had Israel not sinned with the Golden Calf, our sages conclude, they would have received only the five books of Moses and the book of Joshua. For as the verse says, “Much wisdom comes through much grief.”

Remembered and Enacted

These hundred and twenty days have left a lasting imprint on our experience of time. For the Jewish calendar does far more than measure and mark time; in the words of the book of Esther, “These days are remembered and enacted.” The festivals and commemorative dates that mark our annual journey through time are opportunities to reenact the events and achievements which they remember.

Every Shavuot, we once again experience the revelation at Sinai and our acquisition of the blueprint and foundation of our lives. Every year on the 17th of Tammuz, we once again deal with the setbacks and breakdowns epitomized by the events of the day. The month of Elul and the first ten days of Tishrei, corresponding to Moses’ third 40-day stay on Mount Sinai, are, as they were then, days of goodwill between G‑d and man—days in which the Almighty is that much more accessible to all who seek Him.

And Yom Kippur, the holiest and most potent day of the year, marks the climax of the 120-day saga. Ever since the day that G‑d gave the second tablets to the people of Israel, this day is a fountainhead of teshuvah: the source of our capacity to reclaim the deficiencies of the past as fuel and momentum for the attainment of new, unprecedented heights; the source of our capacity to exact a profit from G‑d’s volatile and risky investment in human life.

Based on the teachings of the Lubavitcher Rebbe.